With single gene insertion, blind mice regain sight

Single gene insertion restores light sensitivity in mice with inherited retinal degeneration, pointing to potential human treatment within three years

March 15, 2019

It was surprisingly simple. University of California, Berkeley, scientists inserted a gene for a green-light receptor into the eyes of blind mice and, a month later, they were navigating around obstacles as easily as mice with no vision problems. They were able to see motion, brightness changes over a thousandfold range and fine detail on an iPad sufficient to distinguish letters.

The researchers say that, within as little as three years, the gene therapy — delivered via an inactivated virus — could be tried in humans who’ve lost sight because of retinal degeneration, ideally giving them enough vision to move around and potentially restoring their ability to read or watch video.

A formerly blind mouse treated with the new therapy explores its environment like a normal sighted mouse. UC Berkeley researchers are hoping to produce a similar therapy for people who are blind, providing enough vision to easily move about and perhaps enough to read or view movies. (Photo by Ehud Isacoff and John Flannery)

“You would inject this virus into a person’s eye and, a couple months later, they’d be seeing something,” said Ehud Isacoff, a UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology and director of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute. “With neurodegenerative diseases of the retina, often all people try to do is halt or slow further degeneration. But something that restores an image in a few months — it is an amazing thing to think about.”

About 170 million people worldwide live with age-related macular degeneration, which strikes one in 10 people over the age of 55, while 1.7 million people worldwide have the most common form of inherited blindness, retinitis pigmentosa, which typically leaves people blind by the age of 40.

“I have friends with no light perception, and their lifestyle is heart-wrenching,” said John Flannery, a UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology who is on the School of Optometry faculty. “They have to consider what sighted people take for granted. For example, every time they go to a hotel, each room layout is a little different, and they need somebody to walk them around the room while they build a 3D map in their head. Everyday objects, like a low coffee table, can be a falling hazard. The burden of disease is enormous among people with severe, disabling vision loss, and they may be the first candidates for this kind of therapy.”

Currently, options for such patients are limited to an electronic eye implant hooked to a video camera that sits on a pair of glasses — an awkward, invasive and expensive setup that produces an image on the retina that is equivalent, currently, to a few hundred pixels. Normal, sharp vision involves millions of pixels.

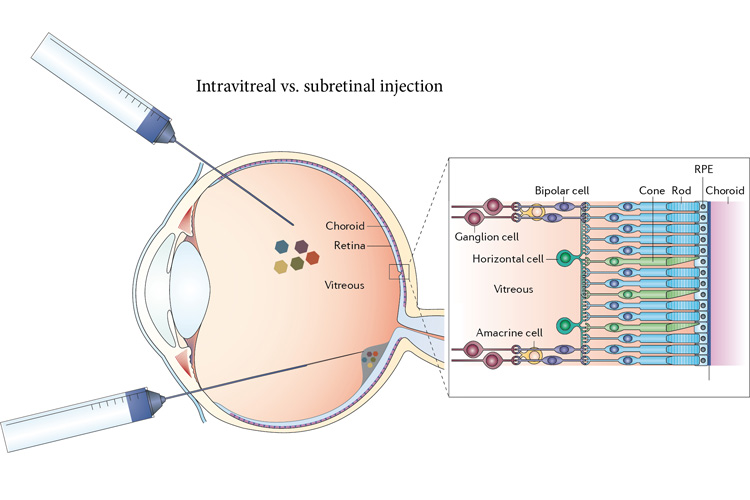

The new therapy involves injecting inactivated viruses into the vitreous to carry a gene directly into ganglion cells. Earlier versions of viral therapy required injecting the viruses underneath the retina (bottom). The gene makes normally ‘blind’ ganglion cells light sensitive, returning sight to eyes that have lost the normal light sensors, the rods and cones. The right image shows the cell layers in a normal retina. (Image by John Flannery)

Correcting the genetic defect responsible for retinal degeneration is not straightforward, either, because there are more than 250 different genetic mutations responsible for retinitis pigmentosa alone. About 90 percent of these kill the retina’s photoreceptor cells — the rods, sensitive to dim light, and the cones, for daylight color perception. But retinal degeneration typically spares other layers of retinal cells, including the bipolar and the retinal ganglion cells, which can remain healthy, though insensitive to light, for decades after people become totally blind.

In their trials in mice, the UC Berkeley team succeeded in making 90 percent of ganglion cells light sensitive.

Isacoff, Flannery and their UC Berkeley colleagues will report their success in an article appearing online March 15 in Nature Communications.

‘You could have done this 20 years ago’

To reverse blindness in these mice, the researchers designed a virus targeted to retinal ganglion cells and loaded it with the gene for a light-sensitive receptor, the green (medium-wavelength) cone opsin. Normally, this opsin is expressed only by cone photoreceptor cells and makes them sensitive to green-yellow light. When injected into the eye, the virus carried the gene into ganglion cells, which normally are insensitive to light, and made them light-sensitive and able to send signals to the brain that were interpreted as sight.

The orange lines track the movement of mice during the first minute after they were put into a strange cage. Blind mice (top) cautiously keep to the corners and sides, while treated mice (middle) explore the cage almost as much as normal sighted mice (bottom). (Photo by Ehud Isacoff and John Flannery)

“To the limits that we can test the mice, you can’t tell the optogenetically-treated mice’s behavior from the normal mice without special equipment,” Flannery said. “It remains to be seen what that translates to in a patient.”

In mice, the researchers were able to deliver the opsins to most of the ganglion cells in the retina. To treat humans, they would need to inject many more virus particles because the human eye contains thousands of times more ganglion cells than the mouse eye. But the UC Berkeley team has developed the means to enhance viral delivery and hopes to insert the new light sensor into a similarly high percentage of ganglion cells, an amount equivalent to the very high pixel numbers in a camera.

Isacoff and Flannery came upon the simple fix after more than a decade of trying more complicated schemes, including inserting into surviving retinal cells combinations of genetically engineered neurotransmitter receptors and light-sensitive chemical switches. These worked, but did not achieve the sensitivity of normal vision. Opsins from microbes tested elsewhere also had lower sensitivity, requiring the use of light-amplifying goggles.

To capture the high sensitivity of natural vision, Isacoff and Flannery turned to the light receptor opsins of photoreceptor cells. Using an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that naturally infects ganglion cells, Flannery and Isacoff successfully delivered the gene for a retinal opsin into the genome of the ganglion cells. The previously blind mice acquired vision that lasted a lifetime.

“That this system works is really, really satisfying, in part because it’s also very simple,” Isacoff said. “Ironically, you could have done this 20 years ago.”

Isacoff and Flannery are raising funds to take the gene therapy into a human trial within three years. Similar AAV delivery systems have been approved by the FDA for eye diseases in people with degenerative retinal conditions and who have no medical alternative.

It can’t possibly work

According to Flannery and Isacoff, most people in the vision field would question whether opsins could work outside their specialized rod and cone photoreceptor cells. The surface of a photoreceptor is decorated with opsins — rhodopsin in rods and red, green and blue opsins in cones — that are embedded in a complicated molecular machine. A molecular relay — the G-protein coupled receptor signaling cascade — amplifies the signal so effectively that we are able to detect single photons of light. An enzyme system recharges the opsin once it has detected the photon and becomes “bleached.” Feedback regulation adapts the system to very different background brightnesses. And a specialized ion channel generates a potent voltage signal. Without transplanting this entire system, it was reasonable to suspect that the opsin would not work.

In a normal retina, photoreceptors – rods (blue) and cones (green) – detect the light and relay signals to other layers of the eye, ending in the ganglion cells (purple), which talk directly to the vision center of the brain.

But Isacoff, who specializes in G protein-coupled receptors in the nervous system, knew that many of these parts exist in all cells. He suspected that an opsin would automatically connect to the signaling system of the retinal ganglion cells. Together, he and Flannery initially tried rhodopsin, which is more sensitive to light than cone opsins.

To their delight, when rhodopsin was introduced into the ganglion cells of mice whose rods and cones had completely degenerated, and who were consequently blind, the animals regained the ability to tell dark from light – even faint room light. But rhodopsin turned out to be too slow and failed in image and object recognition.

They then tried the green cone opsin, which responded 10 times faster than rhodopsin. Remarkably, the mice were able to distinguish parallel from horizontal lines, lines closely spaced versus widely spaced (a standard human acuity task), moving lines versus stationary lines. The restored vision was so sensitive that iPads could be used for the visual displays instead of much brighter LEDs.

“This powerfully brought the message home,” Isacoff said. “After all, how wonderful it would be for blind people to regain the ability to read a standard computer monitor, communicate by video, watch a movie.”

These successes made Isacoff and Flannery want to go a step farther and find out whether animals could navigate in the world with restored vision. Strikingly, here, too, the green cone opsin was a success. Mice that had been blind regained their ability to perform one of their most natural behaviors: recognizing and exploring three-dimensional objects.

Diagram of a setup in which mice were trained to respond to patterns on iPads instead of much brighter LEDs. After the trained mice went blind from an inherited retinal disease, they were treated with a gene therapy that restored sufficient sight for them to respond to patterns on the iPads almost as well as before they went blind.

They then asked the question, “What would happen if a person with restored vision went outdoors into brighter light? Would they be blinded by the light?” Here, another striking feature of the system emerged, Isacoff said: The green cone opsin signaling pathway adapts. Animals that were previously blind adjusted to the brightness change and could perform the task just as well as sighted animals. This adaptation worked over a range of about a thousandfold — the difference, essentially, between average indoor and outdoor lighting.

“When everyone says it will never work and that you’re crazy, usually that means you are onto something,” Flannery said. Indeed, that something amounts to the first successful restoration of patterned vision using an LCD computer screen, the first to adapt to changes in ambient light and the first to restore natural object vision.

The UC Berkeley team is now at work testing variations on the theme that could restore color vision and further increase acuity and adaptation.

The work was supported by the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health, the Nanomedicine Development Center for the Optical Control of Biological Function, the Foundation for Fighting Blindness, the Hope for Vision Foundation and the Lowy Medical Research Institute.